Britain’s charging infrastructure is failing drivers

At Britain’s largest electric vehicle charging hub, drivers use the forecourt wi-fi while they power up their batteries or pass time in the on-site Starbucks. Another customer, new to ultra-fast charging, seeks help to work the machine. Some of the low-charge parking spaces have been rented for the day.

Located at Birmingham’s National Exhibition Centre, off the M42 and close to the city’s airport, the hub can charge 180 electric vehicles simultaneously. In the words of Akira Kirton, the chief executive of BP Pulse, the site’s operator, “we found a dream location”. The operator is part of BP, the oil major, which has committed £1 billion to building infrastructure over the next few years.

However, what made the NEC site ideal also underlines why such hubs are difficult to build. For a start, there was spare land and a willing private landlord. A catchment area of drivers ensures that expensive infrastructure makes a financial return. Crucially, a nearby electricity substation meant an easier connection to the grid and fewer long stretches of costly underground cabling. Although the site had “everything we wanted”, it still took two years of negotiations and a further seven months of construction.

The number of Britain’s public chargers has doubled to more than 57,000 in under four years and the government says it wants 300,000 by 2030, when it is forecasting that there will be nine million electric vehicles on the road, with a 37 million figure given for 2050. Yet, according to David Hall, vice-president of power systems at Schneider Electric, the energy management and technology group, the UK is far from ready. “Consumer concerns over charging infrastructure are bound to have an impact on demand for EVs,” he said. “There are blackspots across the UK where the number of charging stations is nowhere near sufficient to support the number [of the vehicles].”

Government subsidies are being given to local authorities to help to plan the rollout (though not for the NEC hub). This includes the £450 million Local Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Fund. A £950 million Rapid Charging Fund is awaiting distribution.

The charging point industry is increasingly concerned that money is being wasted on easy options, not on what drivers need. One executive told The Times: “What started with good intentions — give councils pots of money and let them get on with it — is now an almighty mess and is distorting the market.” He is consulting lawyers over a council “sitting on” a planning application that cost £40,000 to prepare.

Asif Ghafoor, the chief executive of Be.Ev, a charging point firm, and a founder member of ChargeUK, the industry trade body, said that every company had a “bonkers” example of red tape. “Councils want to set the strategy, direct the strategy, deliver the strategy: it’s not their skill-set,” he said. Many firms felt sidelined in the planning process.

He is no fan of lamppost charging, which is slow because of the low voltages involved and where access often is blocked, anyway, by non-electric vehicles. There are similar reservations about the proliferation of street-side charging boxes, which one disability campaign group warned were “invading pavements”. Phil Shadbolt, the founder of EZ-Charge, which is based in Oxford, said they were frequently vandalised or accidentally damaged by cars and were “an expensive nightmare” to maintain.

There was another issue with street-side charging, said Andy Palmer, a former Aston Martin chief and now the interim chief executive of PodPoint, a home and workplace charging company: “Some residents file planning objections simply because they don’t want cars parked outside their house. There’s a lot of ‘not-in-my-backyard’.”

A rapid expansion of community hubs and pit-stops is urgently needed, executives say. But it will be costly and disruptive. Securing access rights for cabling and infrastructure running through private land “is still quite a challenge”, Ben Nelmes, the chief executive of New AutoMotive, an independent research group, said. “Landowners can block that sort of thing quite easily.”

Ghafoor said there were plenty of suitable unused sites and that councils and landowners must be pressed to release them. Large supermarket car parks could be ideal locations, but the land often was owned by property and pension funds that showed little interest in entering talks, he said.

He believes it is time for changes to planning rules, including allowing more infrastructure under permitted development regulations. Off-road charging hubs will need bigger subsidies than on-street solutions, especially in rural locations, but the greater use of profit-share partnerships with councils and landowners could help to fill funding gaps.

A reason that motorways have received considerable charging investment is because planning can be simpler. Yet even here, a positive environment, motorway infrastructure “has become an obsession” for policymakers, an executive said: “Let’s remember the average car journey is about 11 miles.”

Toddington Harper, the founder of Gridserve, which specialises in motorway chargers, accepts the criticism. He no longer believes that range anxiety is a big issue because motorway infrastructure has improved. “I can understand why people are saying you need to turn your attention to other areas that are not as good,” he said. Rural areas were being left behind because they did not have the commercial viability of busy motorway hubs, Harper said.

According to Schneider Electric, in Cornwall last year tourists accounted for a vast 1,380 per cent rise in the number of electric vehicles and a 1,498 per cent increase in demand for charging points. In the summer months there were approximately 471 electric vehicles per charger. The government said that some money from its next tranche of £950 million in subsidies would support non-commercial areas, but there also would be help for more motorway grid upgrades.

Amid arguments over public charging, Palmer said it was important to remember that 80 per cent of electric vehicles were charged at home and the workplace and would continue to be for many years. “I meet owners who’ve never used a public charger. Not having rapid charging is no great loss,” he said.

Home charging is also cheaper. Public prices vary according to contracts, with electricity suppliers and the need for an investment return. And public charging carries 20 per cent VAT, against 5 per cent on domestic power.

Off-street charging is not available to everyone, especially those without driveways, but perhaps more money could be directed to finding solutions, Palmer suggested. There are already experiments with sinking cable gullies across pavements so that electric vehicle owners can use domestic power without creating trip hazards. Overhead metal frames that keep cables off the ground are another option.

Darren Rodwell, transport spokesman for the Local Government Association, defended councils’ record, saying that they must take into consideration several factors and competing priorities when spending limited financial resources. On-street charging played an important role in the charging mix, he said, adding that councils needed “long-term funding certainty and flexibility”.

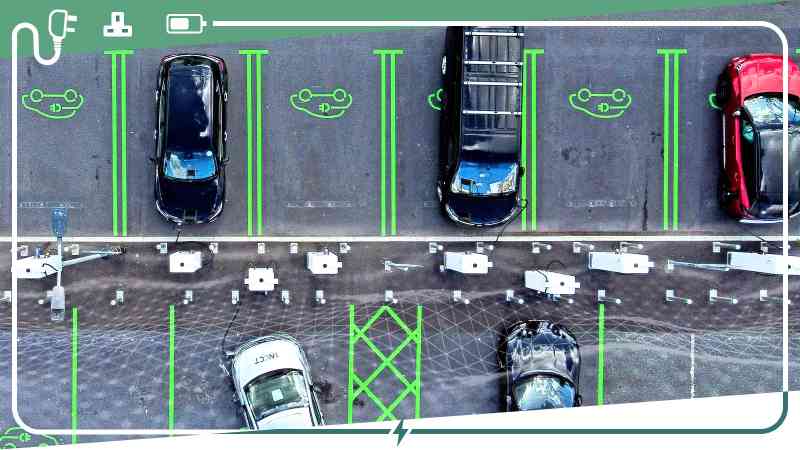

No solution has all the answers. Trial and error was the only way forward in a fast-moving but nascent industry, Nelmes said. What appeared sensible five years ago is not now and hindsight may question today’s solutions. One day, wireless charging plates in the ground may be commonplace, or even on-the-move charging with transmitters at roadsides. The private sector and councils are not working to a rigid plan. “And perhaps this is how we will arrive at an infrastructure that meets people’s needs,” he said.

Can the national electricity grid cope?

After Gridserve installed 12 electric vehicle chargers off the M62 last year it discovered that the local electricity network was not ready for the extra power demand. The charging company had to build a microgrid of batteries and a generator running on biofuel to bring six chargers online, leaving the rest unused.

An executive at another company recalled how plans for a charging hub were scrapped on learning that a retail warehouse full of power-hungry robotics was being built near by. “It soaked up all the spare capacity. We were told upgrading the local network would take a decade,” he said.

It is estimated that more than 37 million fully electric vehicles will be on the road by 2050, from a million today, and that they will increase electricity consumption by 40 per cent, according to Schneider Electric, the technology group. The vehicles will need easily accessible and reliable charging. Will the power grid be ready? There are growing doubts.

Last month the National Grid Electricity System Operator estimated that an additional £60 billion was needed on top of billions already spent on upgrades. About a thousand miles of new power cables, pylons and substation upgrades were needed. A report last year warned that some communities may have to be financially compensated amid fears that the new infrastructure will blight the countryside.

Generating electricity is also changing. Toddington Harper, Gridserve’s founder, said the existing network, made up of a small number of very large power stations run on fossil fuels, was “almost the exact opposite” of what was needed — a decentralised network powered principally by renewable energy. Andy Palmer, the interim chief executive of PodPoint, an electric vehicle charging company, said that moving to wind and solar put more volatility in the electricity network. At present, supply meets demand, but in the future demand may have to follow supply.

There will be additional strain — everything from heat pumps to factories will need renewable electricity. The Grid says that new nuclear power will increase capacity. Smart-charging technology to better use off-peak power and microgrids to store energy also will ease demand. Yet Britain has only a few years to prepare for its net zero targets, not the decades that some experts fear it will really take.

Tomorrow: We look at the future for Motorsport Valley, the 4,000 engineering, technology and component firms linked to racing and the wider automotive market that are based in Oxfordshire and adjoining counties